Across Europe, workers are increasingly voicing concerns about burnout, with many struggling to balance jobs, health, and family life. In Poland, where employees work an average of 1,840 hours per year- one of the highest in the EU – discussions about a four-day workweek are gaining traction. Meanwhile, Greece is sparking controversy with a proposed 13-hour workday, while other nations experiment with shorter workweeks. So where does Malta stand in this debate?

Greece’s 13-hour workday: productivity or exploitation?

The Greek Labour Ministry’s plan to extend daily working hours to 13 for the same employer has drawn fierce backlash. The General Confederation of Greek Workers (GSEE) argues that this will exhaust employees without improving productivity. They insist that working hours should be set through social dialogue, not government intervention.

Labour Minister Niki Kerameos defends the proposal, highlighting a 40 per cent overtime bonus and safeguards like a 48-hour weekly cap over four months. Yet critics question whether such long hours are sustainable for health, productivity, and family life. Christos Goulas of the GSEE Labour Institute points to high-productivity countries like Denmark and Germany, where shorter workweeks are the norm.

Poland’s long hours and the push for change

Poland ranks among the EU’s hardest-working nations, with employees averaging 42.5 hours per week – well above the EU average of 37. Despite this, productivity remains 25 per cent below the EU average, according to Eurostat. Some Polish companies are now trialling a four-day workweek, following successful experiments in Iceland, Belgium, and Spain, where shorter weeks led to higher productivity and better well-being.

Malta’s workweek: stuck in the middle?

Malta’s average workweek is around 37 hours, but activists argue for further reductions. Andrè Callus of Moviment Graffiti advocates for a 32-hour week, saying it would improve quality of life. The General Workers’ Union (GWU) supports the idea in principle, with Secretary General Josef Bugeja stating, “Work exists for people, not the other way around.”

However, Malta’s human-labour-driven economy raises concerns about competitiveness. Mr Bugeja warns that any reduction in working hours must not harm jobs or economic growth.

In 2023, the Office of the Principal Permanent Secretary introduced the ‘Flexi-Week’ scheme allowing public officers to request a four-day work week and spread their hours accordingly. However, this is not the same, as it offers public workers the chance to do the same amount of hours but spread over four days as oppose to five. There have been no independent studies so far on the effectiveness of this model.

However, while this isn’t the same principle as the four-day workweek, which allows workers to actually reduce their hours, it will grant workers a new degree of flexibility.

As Europe’s work culture splits between longer hours and shorter weeks, Malta faces a crucial choice: Will it follow Poland’s progressive experiments or risk Greece’s gruelling model?

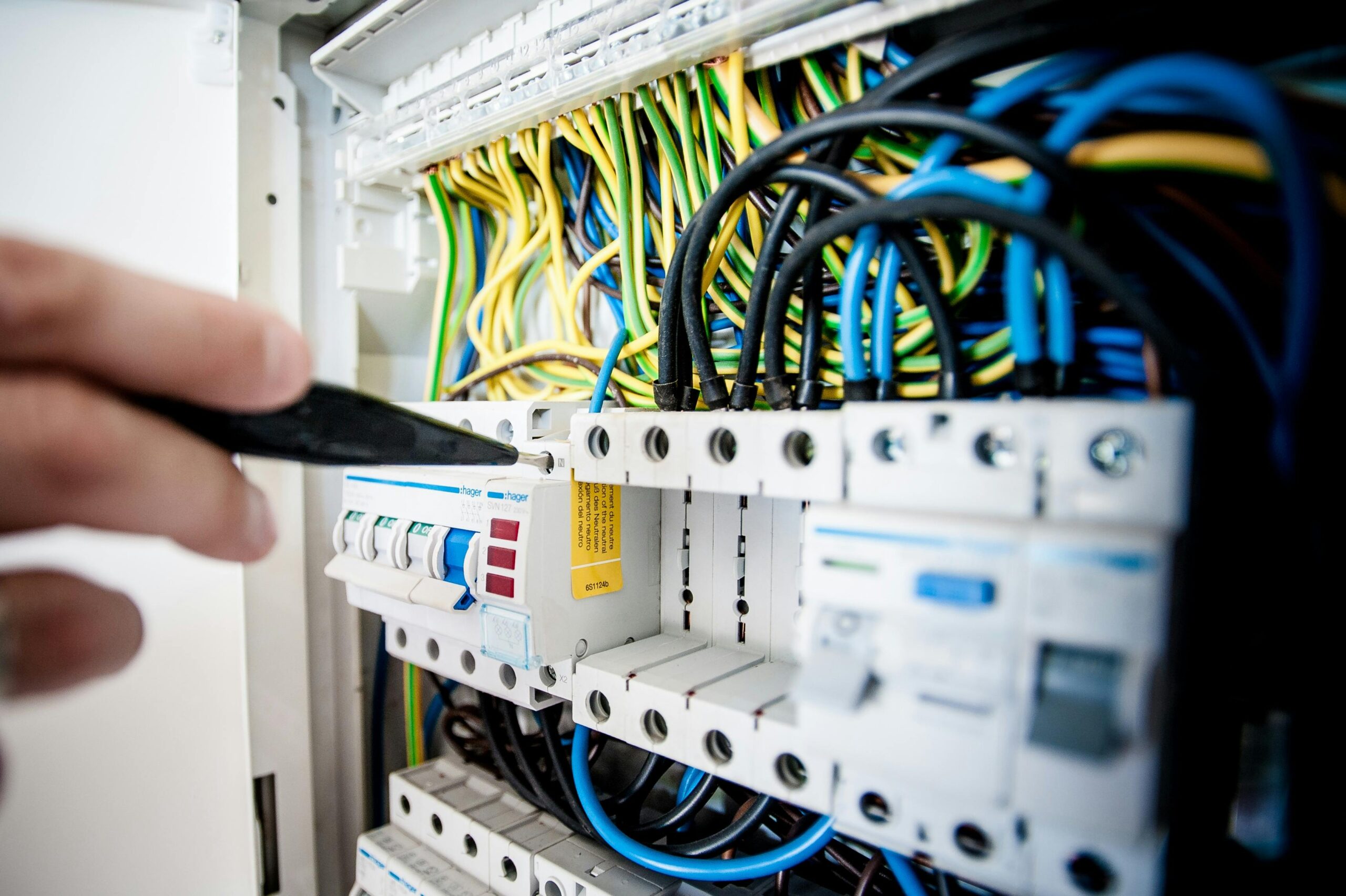

Malta enjoys second lowest electricity prices in the EU

The cost of 100 kWh of electricity ranges from €38.4 in Germany to a low of €6.2 in Turkey

RedCore invests in promising projects: find out more at SIGMA Rome

The international business group RedCore invites SIGMA Rome participants to meet their investment team at its conference stand

Malta’s olive oil cooperative predicts good harvest, but future remains bleak

Malta's olive oil farmers face a number of financial and environmental hurdles