On Thursday (today), the National Statistics Office (NSO) stated that 27.1 per cent of females and 11 per cent of males have experienced sexual harassment at work.

The findings resulted from an NSO survey titled ‘Safety and Well-Being 2022’ which also explored intimate partner violence, non-partner violence, stalking and different experiences faced during childhood.

Overall, a total of 12,000 individuals, aged between 18 and 74 years and living in private households, were drawn from the sampling frame maintained by the NSO (4,800 males and 7,200 females).

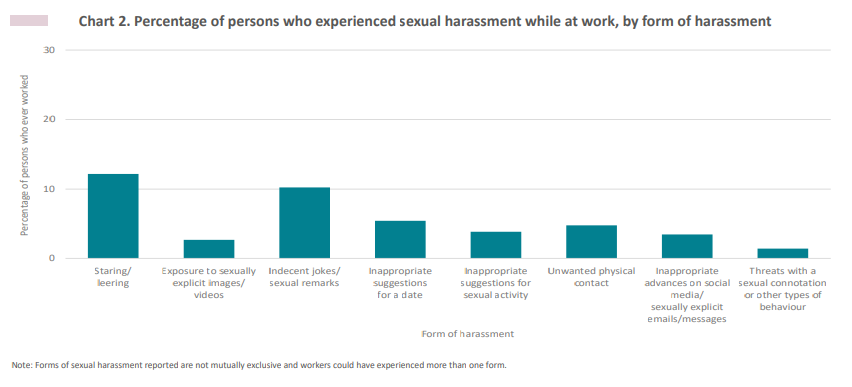

Further figures related to sexual harassment at the workplace show that the most prevalent form was that of inappropriate staring or leering at 12.2 per cent. This was followed by unwanted sexual jokes and remarks at 10.2 per cent and unsolicited physical contact at 4.8 per cent.

Most of the sexual harassment at work had come from co-workers, “with other significant perpetrators indicated as superiors or non employees.”

Intrestingly, more than half (51.6 per cent) the target population of the survey expressed their belief that sexual harassment at work is not common or does not happen at all. Meanwhile, 18.3 per cent believed it is very or fairly common.

“Less than a quarter of females who had ever worked believed that sexual harassment is very or fairly common at the workplace (22.9 per cent),” NSO added.

On the other hand, when asked the same question 14.5 per cent of males who had ever worked believed it is very or fairly common.

When asked about channels that can help victims of sexual harrassment at the workplace, over one-third of persons who had ever worked had no knowledge of help channels available at work. Of those in employment at the time of the survey, 63.1 per cent knew who the contact person responsible for sexual harassment reports at their workplace.

Meanwhile, 36.7 per cent had the availability of sexual harassment training sessions.

How is sexual harassment at work defined in terms of the law?

The People and Standards Division, within the Office of the Permanent Secretary, defines sexual harassment as “unwelcome behaviour of a sexual nature or other sex-based conduct affecting the dignity of women and men at the workplace, or during official duty outside the place of work.”

This is also relevant within the context of natural extensions outside the place of work such as while giving a lift or being given a lift to and from work or while engaging in organised social activities.

In a policy published by the division in November 2022, it highlights that the Occupational Health and Safety Act (Cap. 424) places responsibility on employees to ensure the health and safety of all employees, including their psychological and emotional wellbeing.

While the policy targets workers within the public sector and its clients, it explains different sexual harassment forms that are also relevant to the private sector. Some of which are:

- Physical conduct of a sexual nature – such as unwanted physical touch. Such behaviour can result in the initiation of criminal proceedings.

- Verbal conduct of a sexual nature – unwelcome sexual advances, propositions or pressure for sexual activity, continued suggestions for social activities outside the workplace even though it had been made clear that suggestions are unwelcome, offensive flirtations, suggestive remarks, insensitive jokes, obscene comments, or innuendos.

- Non-verbal conduct of sexual nature: display of pornographic or sexually suggestive pictures (whether by electronic or other means), objects or written materials and making sexually suggestive gestures.

- Sex-based conduct: behaviour that diminishes, mocks, intimidates, or physically harms an employee based on their gender, such as derogatory or degrading remarks, insults related to gender and offensive comments about appearance or attire.

- Sexual blackmail: This involves abuse of authority when somebody holding direct or indirect supervisory or managerial authority, threatens, influences, or takes an employment decision affecting the person harassed.

On the other hand, the National Commission for the Promotion of Equality for Men and Women, through its ‘Sexual Harassment: A Code of Practice’ document, published in 2005, defines it as a prohibited form of gender discrimination. Additionally, it explains that it is unlawful under the Equality for Men and Women Act, 2003 (Cap 456) and under The Employment and Industrial Relations Act, 2002 (Cap 452).

More recently, changes have been in the works to revise the law for sexual harassment at the workplace, that makes it more clear for magistrates and judges when handing out sentences on such cases.

Last December, Justice Minister Jonathan Attard tabled a slight amendment to sexual harassment law which could have wide-ranging impact within the justice system.

This was initiated after a court trial this time last year that cleared a police officer of sexually harassing a 19-year-old colleague.

Even though he passed comments on her physique, placed his hand under her when she sat in the passenger seat and tried touching her leg in the car, Madame Justice Consuelo Scerri Herrera explained that she could not deem this as sexual harassment.

Prior to this amendment, the law stated that a person could only be found guilty of sexual harassment if their behaviour was “offensive, humiliating and intimidating.”

In this sexual harassment case, all three factors had to be proven together for it to be valid. Media reports at the time explained that while the advances were deemed offensive and humiliating, they were not intimidating.

The amendment was voted unanimously in Parliament. When adopted, this amendment would see the law changing to: “A person could be found guilty of sexual harassment at work if their behaviour was offensive, humiliating or [instead of “and”] intimidating.”

At the time, when Minister Attard moved to second reading of the amendment in Parliament, he said that the English text is better aligned with the intentions of the legislator, therefore choosing to amend the Maltese version only.

In that plenary session PN MP Darren Carabott said that it is crucial for the legislators to have “zero tolerance” for sexual harassment in the workplace.

It is why he appealed to the Government to approve the Opposition’s Private Members’ Bill filed in March 2023 so that it makes it obligatory for companies to have an anti-sexual harassment policy in the workplace.

The Bill was also signed by PN MPs Ivan Castillo and Graziella Attard Previ.

The legal changes proposed in the bill would apply to medium-sized and large companies. Nonetheless it still called for firms employing fewer than 49 workers to explore the possibility of introducing such a policy.

The Bill highlighted that this legal amendment would directly affect around 44,000 workers in Malta and Gozo.

BOV’s points to ‘strong governance structure’ as questions resurface about €36 million loan to Steward

The bank also declined to comment on the €400,000 golden handshake given to its former chief risk officer

Malta’s cruise passenger traffic rises during first quarter of 2024 despite decrease in cruise liner calls

Passengers from Italy accounted for 28.4% of the total

‘Unacceptable’: Institute of Journalists condemns PM’s establishment comments targeting the media

Journalists are encouraged to ‘continue with their work without fear or favour’