Following a sharp economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, firms have become increasingly vocal about the labour and skills shortage which has become a major limiting factor for production. But was the pandemic really the cause of the worker shortage in Malta? And would the country have faced similar issues regardless?

A policy note written by Ian Borg, manager in the Economic Projections and Conjunctural Analysis Office of the Central Bank of Malta attempts to understand the real impact of the pandemic on Malta’s labour and skills shortage, and recommends that policymakers should focus on enhancing productivity and redirect market policy strategy to address skills shortages, especially for highly specialised skills.

Mr Borg notes that Maltese firms had been highlighting issues related to labour and skill shortages well before the pandemic period. Indeed, as the Maltese economy registered very strong growth in the years preceding the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, many firms had often complained that they had been finding it increasingly difficult to fill up vacancies.

Official figures show that between 2005 and 2021, labour supply and employment increased by around 75 per cent and unemployment declined from 6.9 per cent to 3.5 per cent in 2021.

Growth in labour supply is largely attributed to both an increase in immigration, and an increase in female labour force participation which was boosted by the introduction of family friendly measures.

This led to an increase in employment across all sectors except manufacturing.

Developments in Malta’s educational attainment between 2005 and 2020 saw the number of early school leavers halve, and the share of the population with tertiary education to treble, leading to a higher educated workforce.

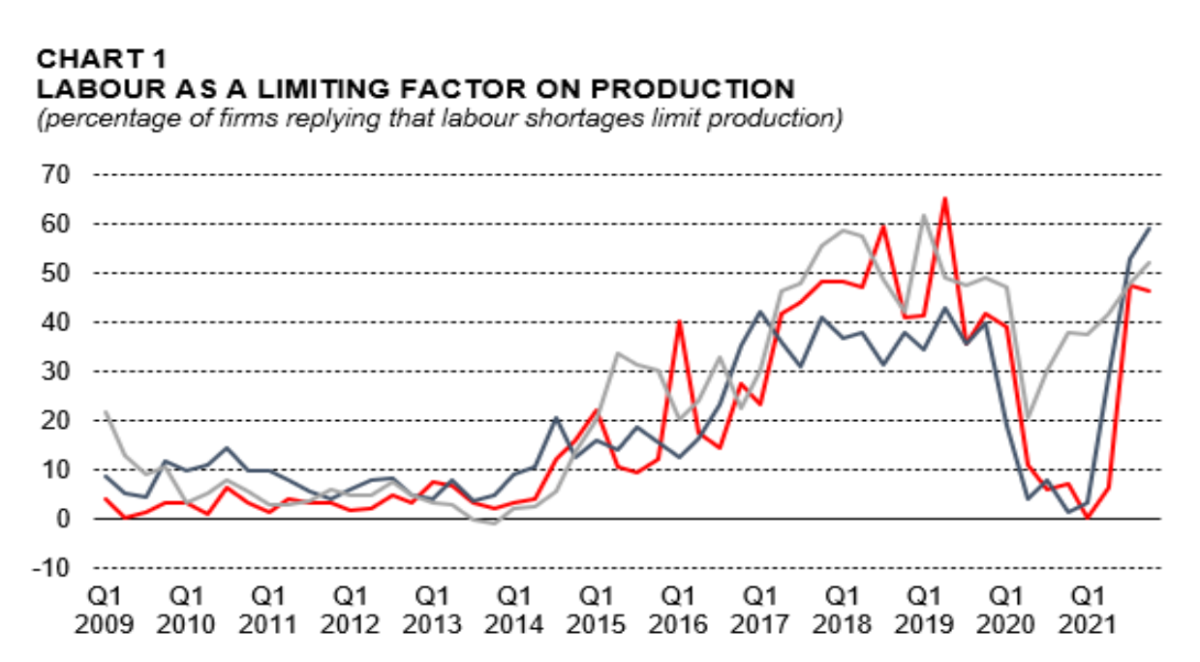

Despite the broad changes, replies to the European Commission’s (EC) business surveys confirms how deeply concerned Maltese firms have been about labour shortages over the past decade.

More than half of all manufacturing firms, and 46 per cent of construction sector businesses considered the labour shortage as a limiting factor to their business activity in 2019.

As the pandemic broke out at the start of 2020, labour temporarily became less of a concern for firms due to activity being shut-down and measures to contain mobility, which dampened demand.

However, as activity recovered to normal levels, firms across all sectors participating in the EC business surveys indicated that by 2021, the labour shortage either reached or surpassed pre-pandemic levels.

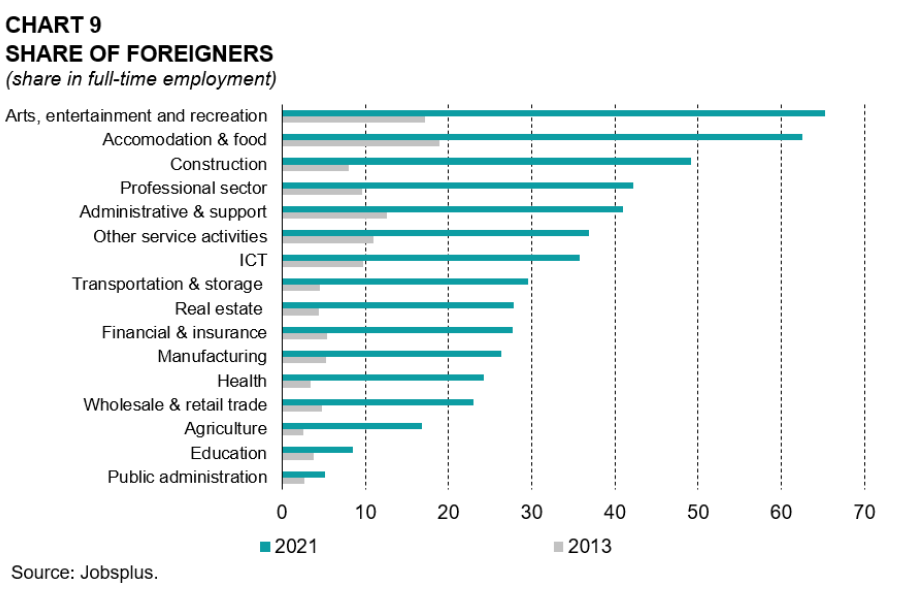

Data presented in the policy note also shows Malta’s growing dependence on foreign workers across all sectors of the economy.

In the arts, entertainment and recreation sector, and also in accomodation and hospitality, foreign workers represent more than half of the workforce.

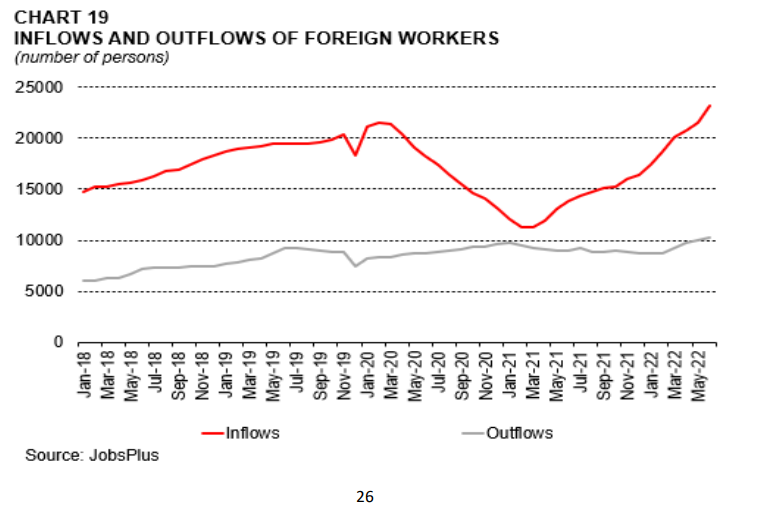

According to official data, the number of foreign workers did not decline even during the height of the pandemic, with inflows consistently surpassing outflows. This data contradicts the sentiment held by businesses that the pandemic led to an exodus of foreign workers.

This was addressed by Finance Minister Clyde Caruana who in 2021 told MaltaToday, “Foreigners did leave but most of those who left were working in the shadow economy and so there were no official records of them. This became apparent when we started paying the COVID wage supplement and employers who had foreigners on their books who did not have a work permit had to let them go because they could not apply for the assistance,”

He estimated that around 10,000 foreign workers who operated in the shadow economy left the country due to the pandemic.

This discrepancy might explain why, despite official data demonstrating a consistent net inflow of foreign workers, as Malta’s economy recovered the labour shortage was on par or in excess of what it was prior to the pandemic.

The policy note also claims that there was no clear evidence of the ‘Great Resignation’ taking place in Malta during the pandemic, which was evident in the US and UK among other countries. The ‘Great Resignation’ is a phenomenon where workers voluntarily resign from their jobs, in hopes of finding a job that offers better conditions and pay.

While the exodus of workers who worked in the shadow economy may not necessarily be considered part of the ‘Great Resignation’ it did unofficially result in a employers losing workers en masse.

Other changes that were brought on during the pandemic was a decline in productivity levels. While participation rates in the economy increased by four per cent in 2021 from 2019, average working hours per week did not.

This could indicate that workers’ preference may have shifted, opting for shorter working weeks in exchange for more leisure time.

This led to a strong rise in productivity per hour in only a few sectors, namely ICT, arts and entertainment, financial and insurance, and public, education and health.

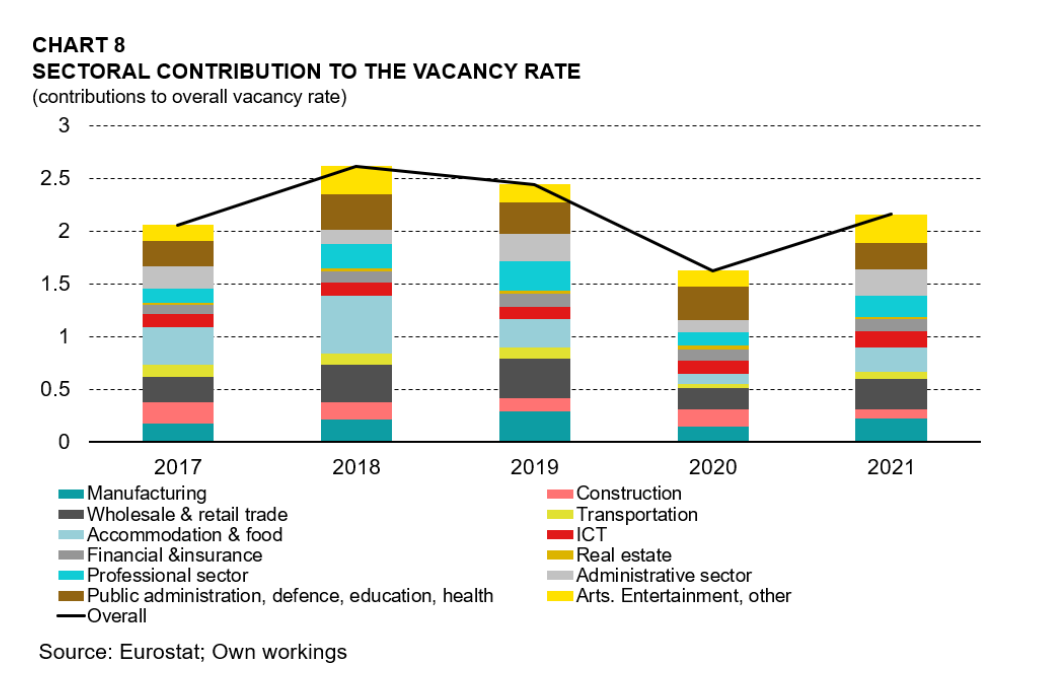

While it may appear positive, a number of those sectors also indicate prominence in vacancy rates, which are most prevalent in the services sectors such as arts and entertainment, IT, wholesale and accommodation, and the professional sector.

The policy note conclusion reads, “policy should be directed towards incentivising sectors and firms that are more productive. This could induce sectoral reallocation towards more productive sectors, which, if combined with reskilling opportunities, can lead to lower shortages. At the same time, educational and labour market policy should be redirected to address skill shortages especially for highly specialised skills.”

Sparkasse CEO Paul Mifsud: ‘We built a bank around a community’

The bank’s history has also been closely tied to Malta’s economic evolution

Free childcare lifted thousands of women out of poverty – Central Bank report

A new Central Bank of Malta study sheds light on the sharp decline in severe deprivation among working-age women

Irrestawra Darek scheme for western Malta oversubscribed in just four days

The scheme provides grants to restore heritage properties and traditional façades