Malta’s fertility rate has been in the gutter for the past number of years, however there has been hardly any discussion on the matter, nor its effects in the long-term.

The fertility rate is the total number of children that would be born to a woman if she were to live to the end of her childbearing years and bear children.

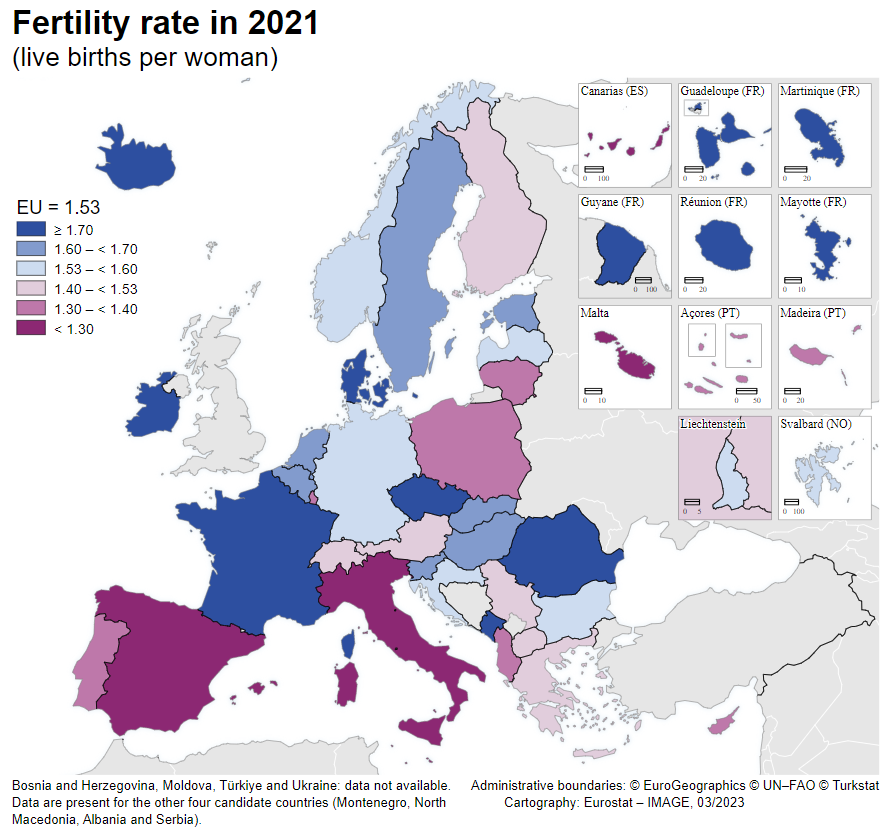

The ideal fertility rate is 2.1, also known as the replacement rate. This is the level of fertility at which a population is capable of replacing itself. However, Malta’s fertility rate of 1.13 not only well below the replacement rate, but is also the lowest in the EU.

This is a problem that is fairly widespread among most developed and advanced economies.

Currently, the lowest fertility rate in the world is registered in South Korea, which sits at 0.78.

A lower fertility rate usually means that the population in the country will gradually get older, leading to a smaller workforce taking care of an ever larger ageing cohort of people. Coupled with a higher life expectancy, Governments with generous welfare systems have to contend with higher healthcare and social security costs paid for by a smaller number of taxpayers.

Another country which is very worried about its low fertility rate is Japan, but theirs is 1.3, not great but better than Malta’s, so why aren’t alarm bells ringing here?

One main difference between European countries such as Malta and Asian countries such as Japan and Korea is the approach to immigration.

Unlike Korea and Japan, Malta and most European countries are fairly accessible to immigrants seeking job opportunities.

Not only is there the European Union which enables the free flow of goods and people between 27 member states with virtually no restrictions, but Malta is aided by the fact that one of its official languages is English.

Furthermore, the private sector has been pushing the Government to speed-up visa applications to address the shortage, and to search for workers from a wider range of countries.

Regardless of whether immigrant workers decide to settle in the country or not, they inevitably contribute to the state coffers through taxation and social contributions.

A recent parliamentary question revealed that the amount of social contributions paid as a result of non-Maltese workers grew from around €30 million to €200 million between 2011 and 2021.

| Year | Contributions from workers | Contributions from employers |

| 2012 | €14,959,700.88 | €15,083,276.09 |

| 2013 | €18,103,632.60 | €18,253,882.40 |

| 2014 | €21,923,114.63 | €22,083,763.14 |

| 2015 | €28,881,148.53 | €29,064,734.61 |

| 2016 | €39,043,697.71 | €39,225,177.69 |

| 2017 | €51,128,816.71 | €51,323,623.86 |

| 2018 | €68,516,324.72 | €68,833,575.19 |

| 2019 | €82,389,891.36 | €82,528,040.49 |

| 2020 | €90,803,089.36 | €91,038,532.67 |

| 2021 | €100,988,257.70 | €101,064,098.10 |

A policy note published by the Central Bank of Malta in 2019 showed that on average, half of the foreigners in Malta leave within a year, and that only 30 per cent of workers remain for more than six years.

Malta’s ever-tightening labour market and shrinking birth-rate mean that dependence on immigration will only increase if the economy is expected to grow. This will inevitably have long-term ramifications for the country’s demographic composition.

Speaking to BusinessNow.mt, Anna Borg, a senior lecturer and former director of the Centre for Labour Studies at the University of Malta, said that the Government needs to look into this issue and establish why the birth-rate has continued to go down in the last few years.

“This needs a comprehensive and thorough investigation so that the government can adopt evidence-based policies to rectify this situation as happened in countries like France and Sweden.”

“The reasons which lead to such situations are varied and complex and if the situation is not taken seriously by the government through a holistic approach to address the shortcomings, things are unlikely to improve.”

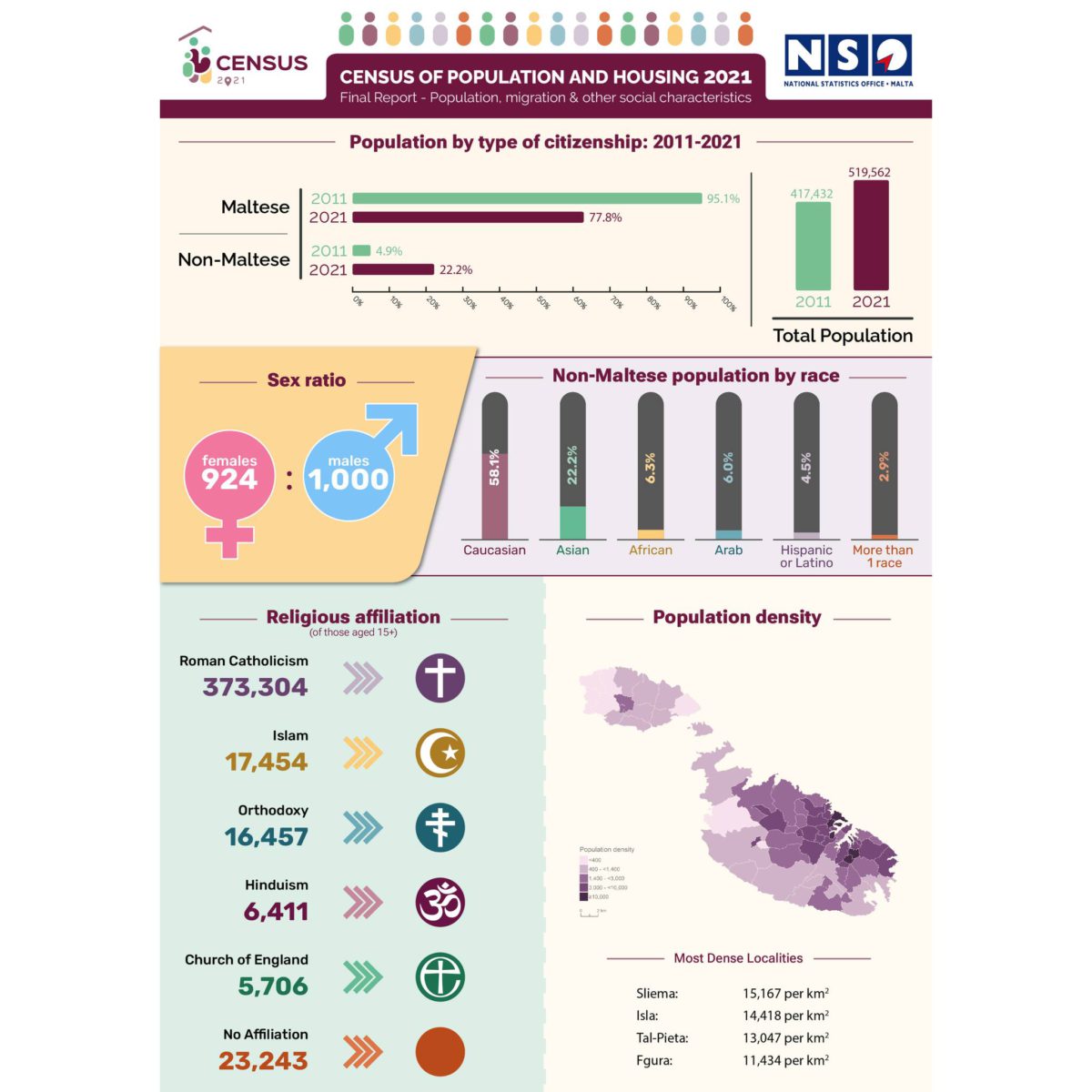

Results from the latest census conducted in 2021 demonstrate that the population grew to 519,562, an increase of over 100,000 compared to 2011 (an increase of 24.4 per cent). Within the same period of time, the share of foreign residents grew from 4.9 per cent to 22.2 per cent.

The effects of immigration have also resulted in a gender imbalance, with 924 females for every 1,000 males.

Another country in a similar boat is Luxembourg. The country has a population of 643,941, and has seen its population grow by 25.7 per cent between 2011 and 2021 according to Eurostat. The share of foreign residents was already high in 2011, at 43 per cent, and has grown to 47.1 per cent in 2022.

The share of foreigners in Luxembourg is most pronounced in its capital city, where the share rises to roughly 70 per cent.

In addition, the country also has to cope with nearly 200,000 cross-border commuters working in Luxembourg, which is facilitated by its position being sandwiched between France, Germany and Belgium.

The country also suffers from a relatively low fertility rate of 1.38, not as but as Malta but still well below the replacement rate.

As long as net annual immigration continues to be above the birth-rate, Malta’s demographics will continue to evolve, but unless the critically low birth-rate is addressed, immigration alone may not be sustainable.

It is also worth noting that, the majority of 16 to 39-year-olds surveyed in 2021 want to live and work in another country, potentially reducing the number of workers available in the country.

With a retirement age of 65 (excluding the option of early retirement) and a life expectancy of 82.5, it is unclear whether the social security contributions provided by immigrants will be enough to compensate for the lack of Maltese workers.

This could potentially lead to the Government creating incentives to boost the birth-rate in the long-term, and also raise the retirement age in the medium term.

In the short-term, the Government already appears to have taken steps in this regard. The Government budget for 2023 included proposals to allow pensioners wishing to participate in the workforce to benefit from a tax cut.

Pensioners who continue to work past the age of retirement may have up to 40 per cent of their pension income excluded from tax purposes.

This may indicate that the Government is opening the door for pensioners who do not want to retire to continue working, and participating in the workforce.

While the short-term solution may work, long and medium-term solutions are far more necessary to mitigate the effects of an ageing population.

db Foundation raises €8,419 for Karl Vella Foundation with MasterChef Malta Charity Dinner

These events form part of the db Foundation's ongoing commitment to supporting vulnerable members of society through impactful initiatives

Residential property prices rise by 5.7% in first quarter of 2025

The new figures show continued growth in Malta’s property sector

Youth4Entrepreneurship Gozo 2025: Youth invited to propose innovative digital solutions

The initiative aims to empower youth to become active contributors to Gozo’s development by addressing local challenges