With higher educational attainment and an increase in female participation rates, women have been seeing their income converging with that of men.

However, policies are needed to ensure women, and parents especially, can still reach their full earning potential, particularly during child-rearing years.

In a report published on the Central Bank of Malta’s quarterly review, senior economist in the economic analysis department of the CBM, Joanne Borg Caruana, explores the state of female participation in the labour force.

Characteristics of female employment

During 2021, the number of women in employment over the age of 15 was 110,900, covering 41 per cent of total employment. 80.2 per cent of them were in full-time employment, with the rest working part-time.

Almost 92 per cent of employed women were involved in the services sector, especially those sectors concerning health, social work, education, and the wholesale and retail industry.

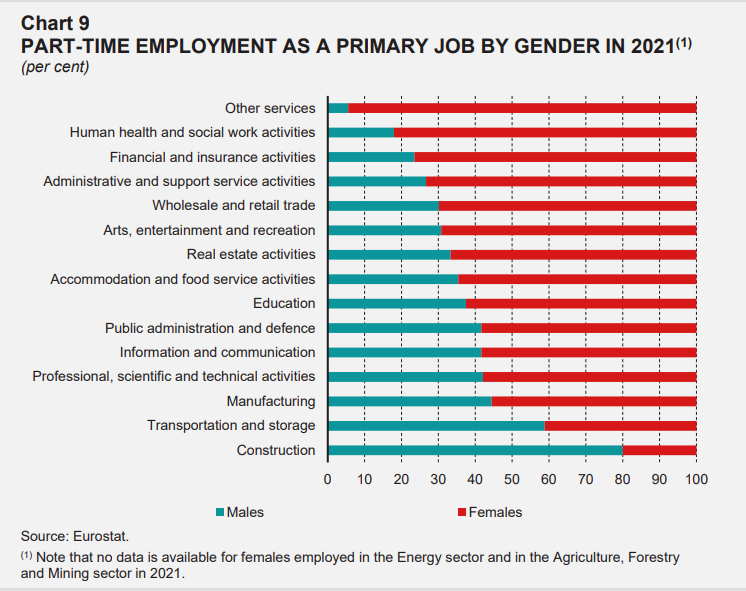

Taking a closer look at part-time work, it’s evident that women dominate the field across most sectors. The main reasons were either due to female students working part-time to supplement their income during studies, or due to older women struggling to find full-time employment. For women in the 25-49 age group, the main reason was either due to family or personal reasons, as well as caring for those with disabilities.

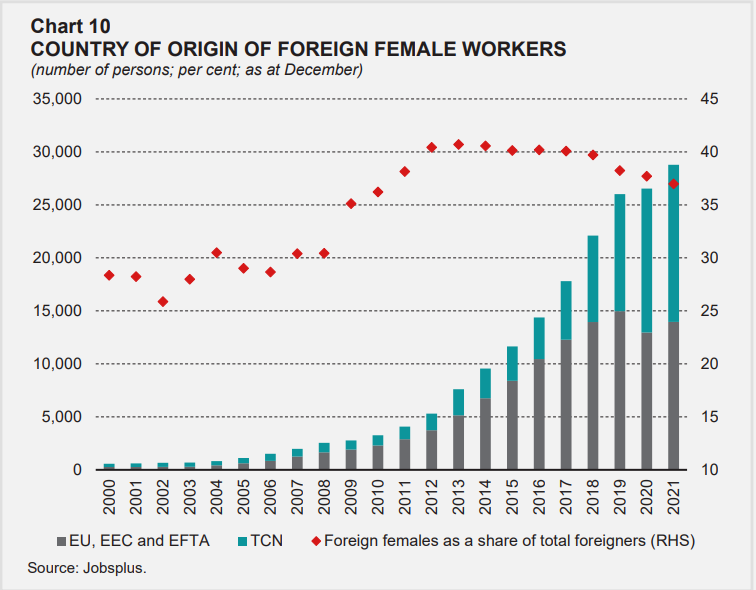

The share of foreign female workers has also grown exponentially, increasing from just 571 workers in 200 to 28,784 in 2021.

The largest number of non-Maltese women with full-time employment was found in the administrative and health sectors.

Participation gap

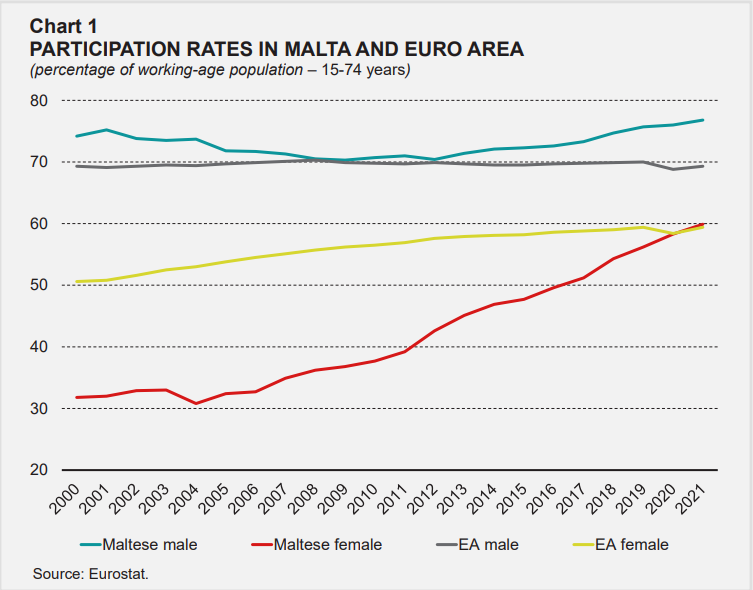

In Malta, the female participation rate has risen strongly since 2005, reaching 59.9 per cent in 2021, exceeding the euro area average of 59.4 per cent. Meanwhile male participation rate fluctuated between 70 – 80 per cent.

This means that over time, the participation rate gap between decreased from 42.4 per cent in 2000 to 16.9 per cent. This is still well above the EU average of 9.9 per cent.

The report noted that the growing rate of female participation is the result of both demand and supply factors. Demand increased through a growing number of service-orientated employment opportunities, and higher educational attainment by women, and supply increased through the introduction of a number of family-friendly policy measures introduced by both Government and businesses.

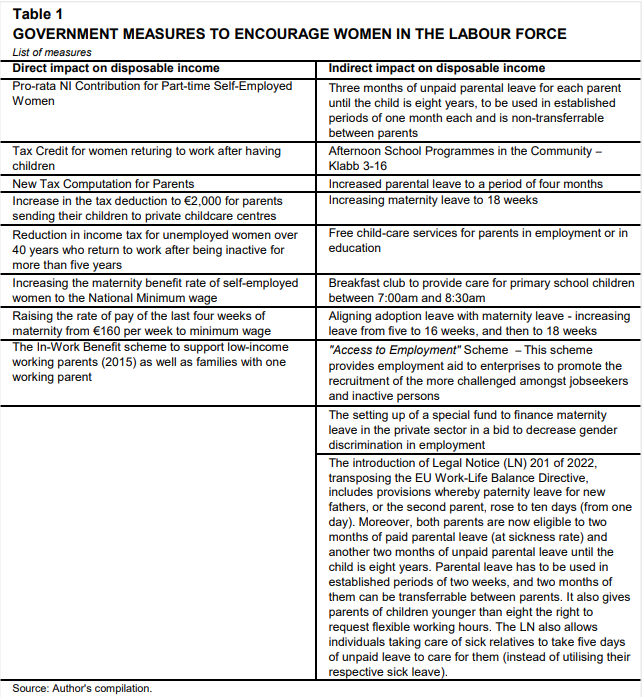

The measures introduced by the Government were divided into two categories: policies which had a direct impact and policies which had an indirect impact on disposable income.

It was noted that the increase of female participation in the workforce may also reflect cultural changes such as a lower fertility rate, increase in the mean age of marriage and first childbirth, higher separation and divorce rates. It may also reflect developments in the housing market, in light of the increase in household indebtedness.

Between 2000 and 2021, the age cohort with the strongest improvement of female participation was the 35 – 39 age group, while the biggest decrease came from the 15 – 24 age group, due to a drop in early school leavers.

However, there was also an increase in employment among older women in response to policy change which increased the pension age. This was found to be more pronounced than among women.

The report noted, “Older women who are in employment appear to differ from the rest of the women in their cohort, and being a much smaller group than older male workers also tend to be relatively more engaged in higher occupational categories and in professional work.”

Nevertheless, overall female inactivity is still significant, and in Malta has always been above the EU average.

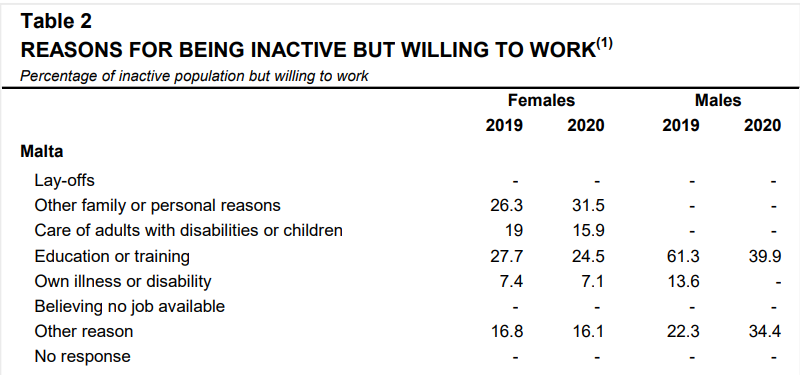

As of 2022, most inactive women were not actively seeking employment (95.4 per cent of 76,700), a smaller rate but higher number than men (97.8 per cent of 49,500). Meanwhile, among those willing to work, the main reasons for inactivity were due to ‘other family or personal reasons’ and because they are in education in training.

It is of note that the number of women willing to work but inactive due to having to take care of other family members or for personal reasons increased during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The time-dimension of the Gender Equality Index published in 2022 by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) shows that, in Malta, as is the case in effectively every EU country, there are far more women doing housework duties and taking care of children and other family members than men.

The report cites a study which claims that one of the reasons for joblessness is unwillingness to work and could be related to the cultural belief that women should stay at home. It is also possible that, there are women who are active, but are classified as ‘inactive’ due to the nature of their work being either temporary or occasional jobs. These jobs usually involve household services such as cleaning and helping run family businesses.

Gender wage gap

Despite higher educational attainment and increased female participation in the workforce, and with laws forbidding employers from discriminating on the basis of gender, the gender wage gap still persists.

Sectoral gender segregation occurs when women tend to work in lower-paying sectors, and occupational gender segregation occurs when men are promoted more frequently than women.

This was could either be the result of glass-ceiling effects, and career breaks.

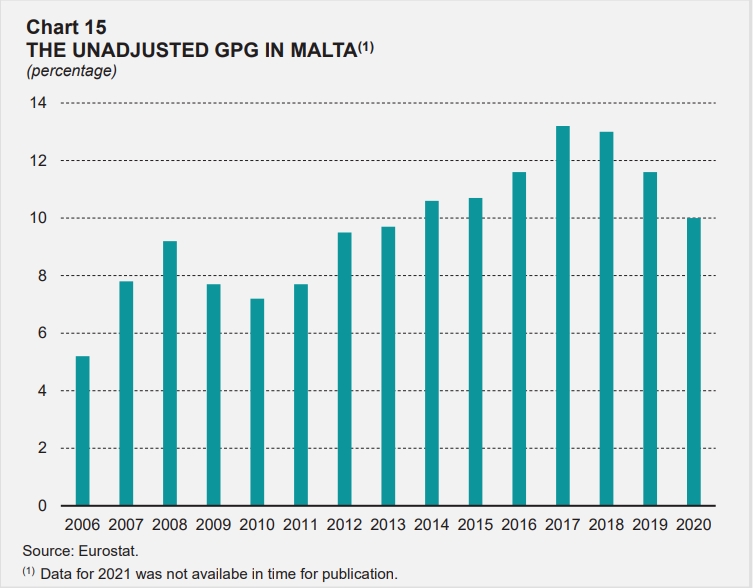

To gauge the income difference between genders, Eurostat disseminates unadjusted gender pay gap data. Up to 2017, the gender pay gap in Malta reached a high of 13.2 per cent and has only slightly declined to 10 per cent in 2022, still well above the historic average.

Although Malta has introduced a number of legislative measures to ensure equal pay for equal work, the gender pay gap is still present in the labour market.

Government introduces mandatory physical inspection for vintage vehicle classification

From 1st September 2025, vehicles seeking vintage status must undergo a physical inspection by the official classification committee

Local filmmakers paid just €250 to screen at Mediterrane Film

The figure stands in stark contrast to the estimated €5 million total spend

Malta International Airport closes in on one million passengers in June

Meanwhile, aircraft traffic movement rose by 4.5 per cent year on year