Plans for an underground heavy gauge train system have long been touted as a way to solve the islands’ ever worsening congestion issues, with short term efforts to solve the problem by widening roads and building flyovers bringing little respite to what has become one of the nation’s most pressing problems.

However, the plans were described as “worrying” by some of the country’s top transportation experts, who warned that the plans more closely resemble a “vanity project” or an “electoral gimmick” than real plans.

Transport Malta’s plan includes 35.5km of track across three lines serving 24 stations. It is estimated to cost €6.2 billion and take 15 to 20 years to build.

In a best case scenario, Phase 1, between Bugibba and Pembroke, would be open by the end of 2029, with construction beginning in 2024. Phase 2, between Birkirkara and Valletta, would be open by end 2033, while Phase 3 could be expected to be completed by end 2036.

“Put simply, this is not we thought the metro would be,” says Bjorn Bonello, president of the Chamber of Planners. “It’s definitely not well thought out. It’s a very superficial way of looking at the metro.”

Noting that the published information so far is all promo, no substance, Mr Bonello would have preferred to wait for the actual studies to be published before commenting, but says that the list of evident deficiencies is so long that it cannot be taken seriously.

“The promotional materials themselves show that it cannot be built,” he argues, noting that issues related to noise, vibrations, geology, hydrology, how the tunnels would affect the water table, were glossed over or ignored while considerable attention was given to how to develop what are currently public open spaces into commercial opportunities.

“No proposal for efficient transport should ever lead to the wholesale destruction of open spaces,” he says, highlighting the fact that open spaces in Paola, Marsa, and Bugibba, among others, looked like they would be developed significantly, while the stations for Naxxar, Mosta, Fgura, and Zabbar would effectively eliminate what are currently public gardens.

He also draws attention to the designs for Balluta, Mosta, and Valletta, questioning how feasible, safe, and publicly acceptable it would be to tunnel far into the rock so close to architectural marvels people travel far and wide to see. Residents of Mosta, for example, set up a petition against a proposal for underground parking close to the town’s monumental basilica, concerned that vibrations during excavation could damage the landmark.

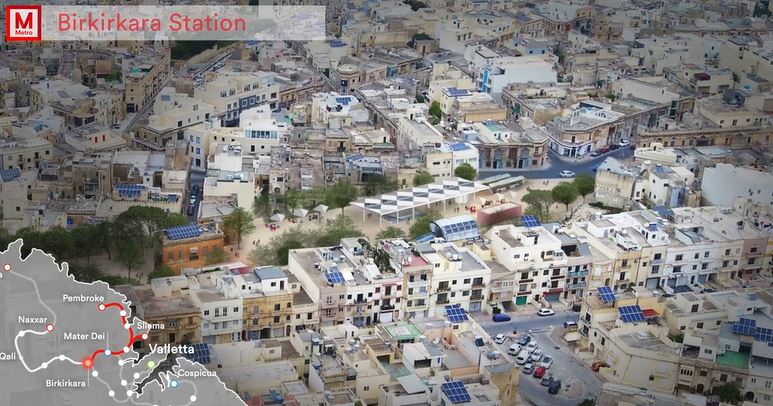

Professor Maria Attard, director of the Institute for Climate Change and Sustainable Development at the University of Malta and head of the geography department, concurs, pointing to the station built next to the Old Railway Station in Birkirkara.

“It’s a garden, a green lung for Birkirkara, getting destroyed for a station.”

Like Mr Bonello, Prof. Attard is waiting for the publication of all the studies commissioned as part of the proposal.

“All we have to go on for now is a glossy brochure. We cannot have a mature discussion about it without the facts in hand.”

One point of particular interest is the reason behind the dismissal of a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) network, a system Prof. Attard has long advocated as the best solution to Malta’s traffic problem.

A BRT network is a system of segregated bus lanes and roadside bus stations that effectively elevates buses’ priority on the roads to ensure they do not get jammed in traffic, making them fast, efficient, and quick and cheap to develop.

“A BRT network can start getting rolled out within weeks, and we could have a full nationwide system by the time the first hole is dug for a metro,” says Prof. Attard. “And it would be many degrees of magnitude cheaper than the figures thrown around for a metro.”

Part of this quick dismissal by Arup, the consultants who have since 2016 been working on the proposal, might have to do with the fact that the team was primarily composed of specialists in rail systems.

However, the official answer is that it “would create issues with car parking and possible congestion”.

Prof. Attard dismisses the claim, and derides the metro as a monument to our “slavery to cars”.

“We are willing to spend €6.2 billion, half our annual GDP, to avoid removing some parking spaces. Spending tremendous amounts of money for a system we’ll need to wait years for. It’s beyond belief.”

Mr Bonello compares the insistence on an underground rail to the famous saying about the hammer and the nail.

“If all you have is a hammer, every problem will look like a nail,” he says.

“Let’s think outside the box. It doesn’t mean grandiose plans. It means exploiting the resources you have, underestimated resources. It’s very easy to get an imported model. It’s more difficult to work in the context you have.

He also questions the timeframe put forward. “We need to look at the reality around us,” he says. “To simply clean up two kilometres of tunnels, traffic was disrupted for most of the summer, and the cladding fell with the first rain.

“We simply do not have a maintenance culture,” he continues. “We let things become unsafe.”

Referring to the frequent power cuts experienced over the summer, Mr Bonello says the Government is putting the cart before the horse.

“There is no silver bullet. A metro will not solve anything. It all ultimately depends on people’s willingness to shift from car to public transport.

“A subway doesn’t give the permeability and capillary reach of buses. That’s why cars are popular – they deliver you to the door. A station a kilometre away will not convince anyone to switch.

“It’s a vanity project that will lead nowhere.”

Buġibba’s Empire Cinema to be transformed into 167-bedroom hotel

St Paul Bay's local council had objected to the plans

Malta-flagged container ship targeted by missiles close to Yemen’s Mokha, British security firm says

Attacks by Iran-aligned Houthi group have had major impacts on global shipping

Employment growth set to halve to 3.2% in 2024 due to slowdown in economic activity – Central Bank

The Central Bank of Malta states that Malta’s labour force grew by 5.1% in the first nine months of 2023